When gossip comes within the arms of a person who reshapes actuality to remain ‘socially proper’

Pakistani dramas have lengthy mastered the artwork of the whisperer. In numerous neighbourhoods — the tight alleys and shared rooftops — there’s all the time that one character: often an aunty. The one who is aware of all, spreads all, and subtly shapes the ethical local weather of all the avenue. The self-appointed guardian of ‘respectability’: the gossip queen.

However Sharpasand modifications that.

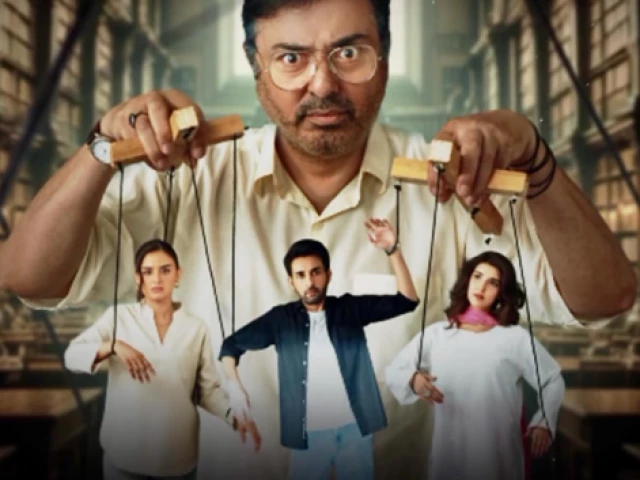

Within the hit drama, produced by iDream Leisure for ARY Digital, the function of the gali whisperer is handed to a person — Farasat Ali, performed by iconic Pakistani actor Nauman Ijaz. That single casting determination transforms all the narrative dynamic.

The title performs on Urdu wordplay: “sharp” and “pasand” loosely counsel somebody agreeable and respectable on the floor, but sharp-edged, calculating and mischievous. Farasat embodies that duality completely.

Nauman Ijaz: Grasp of ethical ambiguity

Ijaz is not any stranger to complicated roles. Over a long time, he has constructed a fame for portraying layered, morally ambiguous characters throughout Pakistani tv. In Sharpasand, nevertheless, he provides us one thing actually unsettling.

His character shouldn’t be loud. He’s not overtly villainous. He doesn’t storm by means of scenes declaring dominance.

As an alternative, he whispers. He suggests. He implies.

One of the placing facets of his efficiency is the sharpness in his gaze — usually accompanied by a slight twitch close to his eye when he senses that he’s shedding management of a story. It’s a bodily tic, however it turns into symbolic: Farasat is pushed by an uncomfortable have to be proper.

Not morally or ethically proper — however socially proper. And if actuality doesn’t align with him, he reshapes it.

A Look into the Story

Alongside his spouse, Rubina (Nadia Afghan) and daughters Eman and Minahil, he builds what can solely be described as a home alliance — a hearsay kingdom. The family turns into a communication hub: info flows in, and most significantly, flows out — edited, flavoured and weaponised.

A lot of it targets younger women within the neighbourhood: sowing suspicion between {couples}, nudging males to query their wives and manipulating older ladies by presenting himself as probably the most rational of all.

A look turns into an affair, a delay in returning house turns into a scandal.

Shazmeen (Hira Mani), who is understood for portraying emotionally clear and susceptible ladies, bears the brunt of this manipulation. Her character’s smallest moments are dissected, reframed, and introduced as ethical proof. A glance exchanged in passing turns into ‘proof’ and a dialog turns into a ‘sample’. And when Farasat makes an attempt to sexually harass her, the narrative is twisted in order that she is introduced because the villain — the lone widow, a financial institution supervisor, and subsequently “too unbiased” for consolation.

Then there may be Sanam (Hareem Farooq) and Fida (Affan Waheed), the final word energy couple, whose relationship turns into Farasat’s slow-burning experiment.

Sanam is succesful. Unbiased. Trendy.

So he shifts the goal — not towards her, however towards her husband.

He befriends Fida. He validates him. He crops seeds of doubt. When Sanam works late, it turns into emotional withdrawal — even perhaps dishonest. When Fida asserts himself, it’s framed as masculinity and rightful authority. Innocent disagreements flip into “patterns.” Farasat doesn’t try to destroy the wedding by means of confrontation, however by means of gradual corrosion.

That’s what makes him harmful.

The deadly weight of gossip

But probably the most devastating arc belongs to Hafsa — whose story ends in demise.

Her destiny underscores the deadly weight of gossip in tightly certain communities. A minor distortion intimately can price a woman her fame. As soon as that’s misplaced, so too are safety, belonging, and validation.

And that’s the horror of Sharpasand.

The drama doesn’t merely present gossip as background chatter; it presents it as a structural power — one able to isolating ladies, destabilising marriages, and even ending lives. By putting a person on the centre of this whisper community, the narrative challenges the frequent trope that ethical policing is a “ladies’s area.”

Right here, patriarchy doesn’t shout. It whispers.

The actual query shouldn’t be how Farasat’s story ends however what number of such whisper networks exist already round us.